A Ugandan, Mathias Kiwanuka, is Playing in the 2012 NFL Super Bowl, For the Giants as a LineBacker

by Ugandan Diaspora Team | January 30, 2012 12:14 pm

By SAM BORDEN, NYTIMES ~ EAST RUTHERFORD, N.J. — Mathias Kiwanuka says he does not remember how old he was when he first found out his grandfather had been assassinated. He struggles to remember the point at which he realized the true meaning of his own last name. He is not certain when he became aware of his family’s importance in African history.

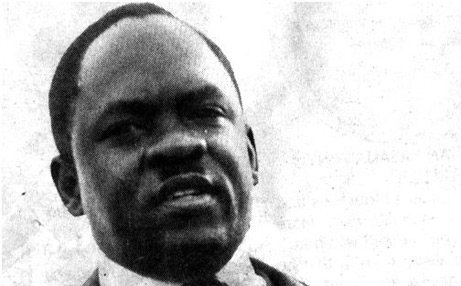

But that is not important, Kiwanuka said recently, because he knows now. He read about his grandfather Benedicto Kiwanuka’s becoming the first prime minister of Uganda and heard about the plight forced upon a man trying to mold freedom out of a society stiffened by chaos. He learned about the pain and suffering Benedicto saw and felt.

And so he knows, too, about Benedicto’s being killed by the despot Idi Amin, a death foretold by some, dreaded by many and seen by experts as a development that set back progress in East Africa for years.

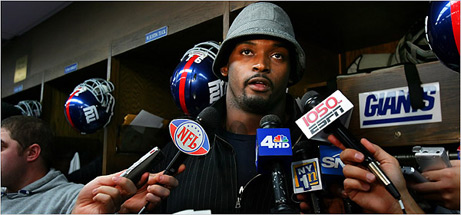

This week, as the Giants prepare to face the New England Patriots in the Super Bowl, Mathias Kiwanuka will be the subject of countless articles and interviews. The reason is obvious: This is his return home. Kiwanuka, now a linebacker for the Giants, was born in Indianapolis. He went to Cathedral High School, a little more than 10 miles from Lucas Oil Stadium, where the Super Bowl will be played Sunday. He won two state championships.

Everyone will want to tell his story, whether it is about his old high school days or how he ended up at Boston College. Old friends will gather around, too, wanting to know about how this season went or how Kiwanuka’s brother, Ben, is doing a year and a half after a horrific motorcycle accident that Kiwanuka witnessed from his own bike just feet away. (Ben is doing well, Kiwanuka said.) Some may even want to talk fatherhood — after all, Kiwanuka and his fiancée are expecting a daughter in March.

It will be the stuff of typical reunions, the memories and reminiscences that exist among people with a shared past. Kiwanuka is clearly excited about it. He began thinking about the possibility of playing in a Super Bowl in Indianapolis years ago, when the game’s site was first announced. He dreamed about it, he said. How could he not?

But Kiwanuka also knows that there is something greater than a birthplace, something more meaningful than the city where a boy learns to read and write and block and tackle. Indianapolis may be his hometown, Kiwanuka said, but Uganda will always be his homeland.

That is why, one day last week after Kiwanuka had answered a barrage of questions about the old days in Indianapolis, he stopped for a moment by a doorway to the Giants’ training center and considered how much being Ugandan could possibly resonate with a kid who grew up in Indiana.

“How much does Uganda mean to me?” he said, his eyes wide. “It means everything.”

Painful Memories

When he was little, Kiwanuka’s parents would talk generally about Benedicto. It was sterile and nonspecific; a young Mathias could glean few details about his father’s father.

“They would say, ‘He was a great man’ and ‘He fought hard,’ ” Kiwanuka recalled. “They would leave it at that.”

Kiwanuka did not press; it was only when he was older that Kiwanuka realized the glossing over was not only intended to spare him from gory details, but also to spare his parents the pain of reliving the experiences of the land they had left behind.

His father, Emmanuel, a political activist, and his mother, Deodata, a nurse, fled Uganda when the country was under Amin’s tyranny. They married in the United States and had three children: Ben, Mary and Mathias, who was born in 1983, 11 years after his grandfather was murdered. His parents separated when he was in sixth grade.

Kiwanuka remembers seeing pictures of his grandfather — “The man in the dress uniform,” he said — but did not fully understand the meaning of Benedicto’s life until he read about him in middle school.

Only then did he realize that his grandfather had been an officer in the Ugandan army during World War II. Or that Benedicto studied law in Britain before becoming a lawyer in Uganda in the late 1950s. Or that after Uganda won internal self-government from Britain in 1962, he became the country’s first prime minister, a voice shouting for democracy.

Benedicto was soon voted out of office, however, and then, years later, imprisoned by Milton Obote, the man who defeated him. But after Amin’s coup in 1971, Benedicto was released and chosen by Amin to become Uganda’s chief justice. According to Dr. Mwangi Kimenyi, the director of the Africa Growth Initiative and an Africa expert at the Brookings Institution, Benedicto is often referred to today as “Justice Kiwanuka” because of his devotion to the law.

“It was this devotion that led to his death,” Kimenyi said in a telephone interview.

“He did not want to go along with Amin’s tyranny and disregard for the law,” Kimenyi continued. “He was even told — if you do not go along with this, you will be killed. But he was a strong man, a committed man. He knew what was right. And even though he would not have been killed if he supported Amin, he knew he could not do it. So Amin’s people took him and killed him. And it was a great, great tragedy.”

Benedicto was murdered on Sept. 22, 1972, and Kimenyi recalled that he was in high school in Kenya at the time. “The whole school was shocked — people were talking about it,” he said. “Even now, Benedicto is a household name in East Africa. He is, without a doubt, one of the most important people in Ugandan history. He stood for a united Uganda. We don’t know what would have happened if not for him. And we don’t know what might have happened if he had lived a full life.”

An Inspiring Trip

Two years ago, Kiwanuka traveled to Uganda during the N.F.L. off-season. He was joined by some family members and a former teammate, linebacker Kawika Mitchell. Kiwanuka had been to Uganda before — he went for the first time in third grade — but this trip was different. Instead of being shocked by the sights and smells of a struggling society as he was when he was a boy, he wanted to use his fame and money to help. His goal, he told Mitchell, was to bring clean, running water to a school in the village where his mother’s family lived.

Mitchell recalled arriving at the school and being stunned. Many of the buildings seemed to be fashioned out of clay, he said, and in one corner of a classroom was a stream of termites eating their way through the floorboards.

The children, though, flocked to Mitchell and Kiwanuka. They did not know about the N.F.L., did not know about where these men had come from. “They just knew we were trying to help them,” Mitchell said in a telephone interview.

“They knew the name,” Kiwanuka said. “They were very respectful. It was amazing.”

Many of the students took part in a ritual ceremony for the visitors, welcoming them to the school. As the students danced, Mitchell looked over and saw Kiwanuka’s face. “He was touched,” Mitchell said. “You could see what it meant to him to be there.”

Mitchell, who played with the Giants in 2007, said Kiwanuka talked often about his heritage even before the trip. When he was a freshman at Boston College, Kiwanuka visited his sister in Washington and purchased a Ugandan flag, which hung on the wall of his room until he graduated.

Kiwanuka also has a large tattoo on his back of Uganda’s governmental seal — a reminder of the importance his grandfather once held in a place so far away.

The point, of course, is to never forget, and Kiwanuka has vowed he will not. Yes, he has a game this weekend, and yes, this week will be about nostalgia and memory, with Kiwanuka starring in all the stories.

But Mitchell said he and Kiwanuka had already spoken about another trip to Africa — “sooner than later,” they told each other — and for someone with a lineage like Kiwanuka’s, it will be a journey full of meaning. It will be more than a return to a hometown; it will be a return to a homeland.

Source URL: https://www.ugandandiaspora.com/a-ugandan-mathias-kiwanuka-is-playing-in-the-2012-nfl-super-bowl-for-the-giants-as-a-linebacker/